Timeline

With the nest cams, we watch the day-to-day lives of ospreys and their chicks. Each day has a rhythm--fishing, feeding, slicing, and sleeping--but the whole season has a pattern, too. Learn more about an osprey's year in this timeline.

An Osprey's Year

Arrival

Osprey pairs arrive in the Clark Fork River valley in late spring after flying thousands of miles from their wintering grounds. See examples of migratory paths here at the Raptor View Research Institute.

Since the first camera was installed in 2010, arrival has been an exciting event at the Hellgate Canyon nest. The first two years, the female appeared around April 1st and the same male showed up nearly two weeks later to immediately begin nest improvements and courtship. In 2012, the nesting pair reunited around April 10th—but the very next day the male disappeared. The female, Iris, was seemingly left on her own for the season. Then on May 7th Iris met Stanley (aka Stan, Stan the Man, the “fishing machine.”)

An early "dating" picure of Iris and Stan in May 2012.

In 2013, Iris again arrived in early April and a different male osprey showed up to court her. Stan chased him away and destroyed the three eggs several weeks later when he arrived on May 3rd.

At the Dunrovin Ranch in 2011, the year we installed the first nest camera, the pair mysteriously disappeared for about a week, before the female returned with what appeared to be a different male. The same pair has now been occupying this nest for three breeding seasons.

Dunrovin "Family Portrait" in June 2013; adults are Harriet and Ozzie.

Courtship and Nest Building

Mating pairs are said to stay together for life and return to the same nest year after year. However, osprey life is dangerous – and just a few years of camera observations show that ospreys don't waste much time before settling on a different partner if one mate doesn't make it.

For example, when Iris meant Stan, there was no dilly-dallying. Stan was pretty serious, too, because he showed up with a fish. Lady ospreys prefer a good provider over flowers or chocolate, and feeding is part of the courtship ritual along with nest-building and mating.

Stanley flies in with dry grass for the nest cup; iris wonders where to put it. Photo courtesy of William Munoz.

“Nestorations” involve building up bigger sticks along the outside rim to protect the soft nest cup inside. The Hellgate nest is about a meter across and one-half to two-thirds of a meter tall. The Dunrovin nest is larger and much deeper--sparrows and starlings burrow nests into it! All sorts of materials are used; baling twine is a problem, but other less dangerous human materials get brought up, like the purple Crown Royal bag in 2012. We have found other exotic items in osprey nests, including plastic fencing, barbed wire, adult magazines, bikini tops and toothpaste.

Check out the log, leafy tree branch and purple Crown Royal "blanket" on the Hellgate Canyon nest.

Eggs and Incubation

Female osprey lay one to four eggs, which are about the size of large chicken eggs and speckled brown.

Close-up of osprey eggs; adult talons and legs for scale.

There is only one brood each year. Egg laying usually happens in late April, early May and incubation takes about 36-42 days. The females do most of the incubating and males bring in fish and sticks for the nest. They do switch periodically. Ozzie at the Dunrovin Ranch nest has been known to yank his mate Harriet off the nest to get a chance to incubate. Stanley doesn't seem to be patient enough for this job. He seems to never get done moving sticks or re-arranging decorative items such as his famous purple blanket and Sensodyne toothpaste.

Hatching

Towards the end of incubation, the eggs show signs of “pipping” where the baby bird has started to break through the shell. These start as little holes and finally give way into larger cracks the chick can emerge from.

Hatching usually occurs in June, but exact dates vary. This is partially due to seasonal differences, but also has to do with hatching asynchrony. Unlike robins and other birds, ospreys start incubating as soon as an egg is laid instead of waiting for all the eggs. This means the first egg has the advantage, which is an evolutionary adaption for a species that has to deal with large, unpredictable swings in food supply each year. In years of scarcity, hunger in the chicks triggers competition and aggression, and the larger chicks harass the smaller chicks. In some cases, this can lead to siblicide. In years of plenty, however, the chicks are just different sizes and there is enough food to go around.

Notice the hole on top of the closest egg--example of pipping.

Nestling Period

The nestling period extends from hatching to fledging. The chicks are fed by their parents and can only waddle around the nest. The parents stay close during this time because not only are the chicks vulnerable to predators, but they can’t regulate their temperature yet. The female often works as a “mombrella” to provide shade from the sun and cover in the rain.

Feeding & Hunting

Just after hatching, the fuzzy little chicks can barely hold their heads up. But they learn to do so quickly and hold their beaks wide open for bits of fish. For over a month, the parents directly feed the chicks. Eventually, the chicks can peck at the fish and feed themselves.

Feeding can sometimes be a frenzy in the nest. Usually, the largest chick gets fed first and when she’s full—as shown by a bulging crop like in the photo—her smaller siblings get to eat. The parents eat what is left and often fly away with the fish.

Ospreys are designed for fishing and excel at hunting in streams and lakes.

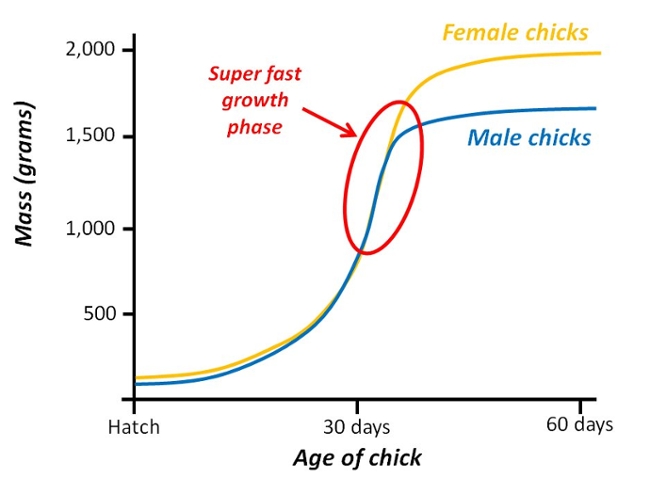

Sigmodial Growth

The chicks grow fast. Most birds grow this way, which is a "sigmoidal growth curve" or "S-shaped growth curve." This graph shows schematically how these osprey chicks grow - pretty slowly when they are small, then at an accelerating rate, and then slowing down as they approach adult size. Female chicks get bigger than male chicks. During the fast growth stage, it seems like the size difference between morning and evening is apparent, like watching bamboo shoots grow. This slows down, though, as the chicks approach their full adult size. There is a noticeable difference between the Dunrovin Ranch and Hellgate Canyon 2013 broods.

And how big are adults? Raising chicks is hard work and energetically stressful, and female ospreys usually lose about 10% of their body mass from the start to the end of the breeding season. Males lose less body mass, but still lose a fair bit. Iris at the Hellgate Canyon nest probably loses about 200 grams from May to August.

Preening & Feathers

Ospreys change their clothes - molt their feathers - just once a year. In the picture from Hellgate Canyon, most of Iris' feathers are about a year old, and some of them are getting tattered and ratty around the edges. She is starting to replace some of her feathers. This is a gradual process of dropping just a few feathers and regrowing new ones in well-organized waves.

All birds spend a lot of time preening, which keeps the feathers in good shape and spreads protective oils on them. Here you can see how well the barbs on Iris' primary feathers, the big flight feathers on her wings, are all perfectly lined up. This is because of careful preening on her part.

When the chicks start preening, it’s a big deal, sort of like toddler teething. The chicks start preening as their feathers begin to push out, which is presumably a pretty itchy process. Once their feathers are out they spend a lot of pushing, brushing and running their beaks through them to keep them in good shape in preparation for flight.

Fledging

A chick’s first voluntary flight off the nest is called fledging. Flight can be a bit wobbly at first, and may include a couple crash landings, but like a kid learning to ride a bike, a chick catches the feeling of the motion pretty quick. Once the birds fledge, they stick around the nest but may not be on camera much of the time.

Fledging occurs about 60 days after hatching, though it depends on the chick and their development. In 2010, the first Hellgate chick took first flight on August 6th; its sibling didn’t take wing for another 11 days. In 2011, the chick fledged on August 7th. In 2012 amd 2013, the chicks hatched later, so they didn’t fledge until mid-August. The Dunrovin broods have tested their wings earlier, with the chicks fledging two weeks before Hellgate in 2013.

Watch this video of Miles fledging in 2013--both chicks do a lot of "wingersizing" or "flappersizing" before take off.

Migration

The ospreys stick around as little as four weeks and as much as seven weeks after fledging. The chicks still get fed by their parents, though they start to learn to hunt on their own. Typically, females leave before their mates, who stick around and keep feeding the chicks. In 2012, Stan from the Hellgate Canyon nest and his chick, Crown Royal, stuck around Missoula through the end of September. Iris and the other two chicks, Hook and Squish, left early in September.

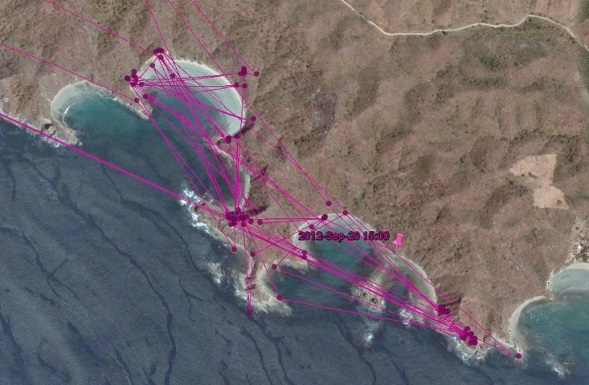

During migration, the nesting pair and their chicks split up. To see some of the southward paths a few Montana ospreys have taken, check out the Raptor View Research Institute’s tracking program.

Wintering

Ospreys travel a long way south. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology tracked one osprey from Massachusetts to French Guinea--a distance of more than 2,700 miles. The Raptor View Research Institute tracks a few Clark Fork River ospreys. Here you can see where they winter. Life is still tough even when you spend all winter in a Nicaraguan bay!

This picture is a series of flights by a female osprey from the Bitterroot Valley in a Nicaraguan bay during September 2012. Image courtesy of Raptor View Research Institute.